Author

Brett Anthony Collett

Health Policy Intern

Navigate the Report

The Scale of the Loss – The Effect of Loss on Children – What Children Need – Focusing Support in Texas

More than 950,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 since the pandemic began in March 2020, which is more than double the number of Americans who died during the two World Wars combined. Many of these were caregivers who left behind children.

While the death of a parent or caregiver for someone aged under 18 is not a rare event, there has not been a time in American history when so many children have lost their caregivers in such a short period of time due to one event. The latest estimate by the Imperial College London suggests more than 200,000 American children have lost a primary caregiver to date, while more geographically specific data from last November shows Texas ranking among the states with the highest rate and total number of caregiver loss in the nation.

Beyond the economic costs and overall death toll of the virus, our concerns around children and COVID-19 have largely centered on school closures and school masking policies. In both the public consciousness and public policy arena, our country has not paid enough attention to the impact of the pandemic on children who have lost a caregiver to the virus—particularly if that child has lost their sole caregiver or if they are from a community that was already disproportionately vulnerable to the pandemic.

Two reports have outlined the scale of this problem and its potential negative outcomes: COVID-19–Associated Orphanhood and Caregiver Death in the United States, which first measured the scale of the problem geographically and demographically up to the summer of 2021; and Hidden Pain, which updated the numbers to November 2021 and outlined possible ways to support these children and reduce the ongoing impact of their traumatic loss. Our analysis is based on these two reports.

The effects of this mass caretaker loss will be felt for decades to come across the country, but will disproportionately affect children who were already facing structural and social barriers. How governments at all levels respond to this crisis, and how quickly, has the power to shape the future for thousands of children who have lost a caregiver to COVID-19—particularly for children of color from low-income households. This report explores the scale of loss, potential impacts on children, and recommendations to support these children.

Author

Brett Anthony Collett

Health Policy Intern

Navigate the Report

The Scale of the Loss – The Effect of Loss on Children – What Children Need – Focusing Support in Texas

More than 950,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 since the pandemic began in March 2020, which is more than double the number of Americans who died during the two World Wars combined. Many of these were caregivers who left behind children.

While the death of a parent or caregiver for someone aged under 18 is not a rare event, there has not been a time in American history when so many children have lost their caregivers in such a short period of time due to one event. The latest estimate by the Imperial College London suggests more than 200,000 American children have lost a primary caregiver to date, while more geographically specific data from last November shows Texas ranking among the states with the highest rate and total number of caregiver loss in the nation.

Beyond the economic costs and overall death toll of the virus, our concerns around children and COVID-19 have largely centered on school closures and school masking policies. In both the public consciousness and public policy arena, our country has not paid enough attention to the impact of the pandemic on children who have lost a caregiver to the virus—particularly if that child has lost their sole caregiver or if they are from a community that was already disproportionately vulnerable to the pandemic.

Two reports have outlined the scale of this problem and its potential negative outcomes: COVID-19–Associated Orphanhood and Caregiver Death in the United States, which first measured the scale of the problem geographically and demographically up to the summer of 2021; and Hidden Pain, which updated the numbers to November 2021 and outlined possible ways to support these children and reduce the ongoing impact of their traumatic loss. Our analysis is based on these two reports.

The effects of this mass caretaker loss will be felt for decades to come across the country, but will disproportionately affect children who were already facing structural and social barriers. How governments at all levels respond to this crisis, and how quickly, has the power to shape the future for thousands of children who have lost a caregiver to COVID-19—particularly for children of color from low-income households. This report explores the scale of loss, potential impacts on children, and recommendations to support these children.

The Scale of the Loss

The latest figures from the Imperial College London estimates in the United States, as of April 2022:

- More than 243,000 children had lost a caregiver to COVID-19

- More than 207,000 children had lost a primary caregiver

The Hidden Pain report breaks down the scale of caregiver loss by categories such as age, race, and category of caregiver. In the United States, as of mid-November 2021:

- More than 70,000 children had lost a live-in grandparent

- More than 13,000 children lost their sole caregiver

Like the overall COVID-19 death toll, these numbers are conservative estimates. It is likely deaths of caregivers due to COVID-19 are underreported.

The rate of loss is not uniform across class or race. Children of color are more likely to have experienced the loss of a caregiver. Compared to white children:

- Native American children are nearly 4 times more likely to have lost a caregiver

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander children are more than 3.5 times more likely to have lost a caregiver

- Hispanic children are 2.5 times more likely to have lost a caregiver

- Black children are nearly 2.5 times more likely to have lost a caregiver

- Asian children are more than 1.5 times more likely to have lost a caregiver

Data from Hidden Pain report, November 2021.

“The lack of racial equity across our economic, social support, and health systems have exacerbated both the risks and scale of loss associated with COVID-19 in these communities.”

The lack of racial equity across our economic, social support, and health systems have exacerbated both the risks and scale of loss associated with COVID-19 in these communities. Black and Hispanic workers are more likely to have been in low-paying “frontline” jobs throughout the pandemic, with higher risk of exposure and little-to-no access to health coverage. Those in states like Texas that have not expanded Medicaid coverage are less likely to have access to affordable, consistent, and reliable care, which increases likelihood of underlying conditions that are associated with COVID-19 deaths. The majority of people with no access to Medicaid or any other form of insurance are Black, Hispanic, or Asian. These structural barriers, coupled with the higher rates of sole caregivers and multigenerational households among Black and Hispanic families compared to white families, have meant children of color are more likely to have lost a sole caregiver or a live-in grandparent.

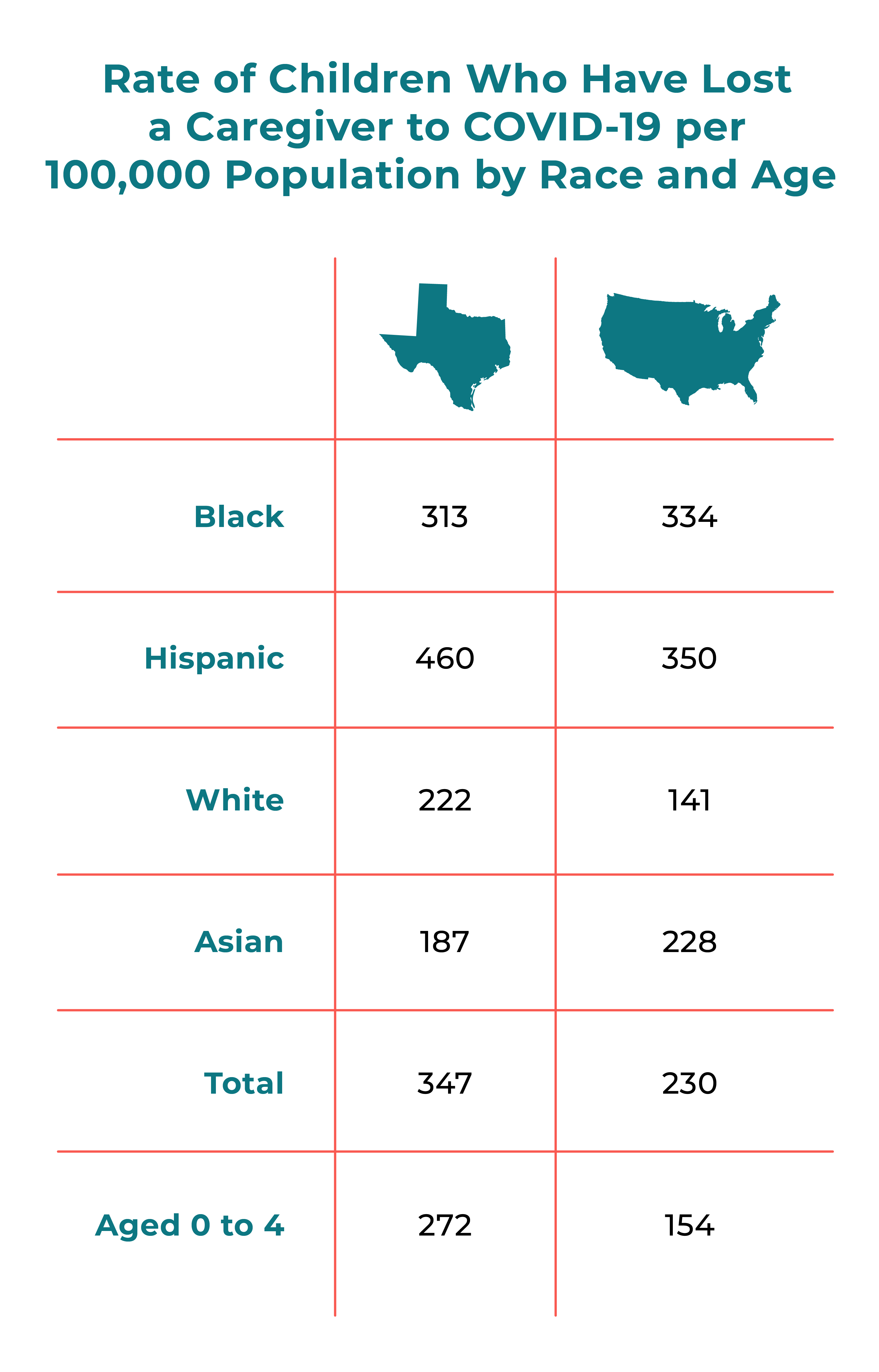

The issue of caregiver loss is particularly acute in Texas, which has the second-highest overall number of caregivers lost to COVID-19 (marginally behind California) with more than 25,600 bereaved children, and the fifth-highest rate of loss per 100,000 children. Texas is the only state to rank among the top five in both measures.

Our state has seen more than three times the number of Hispanic children lose a caregiver compared to white children, and more Black children lose a caregiver than white children despite there being three times more White Texans than Black Texans.

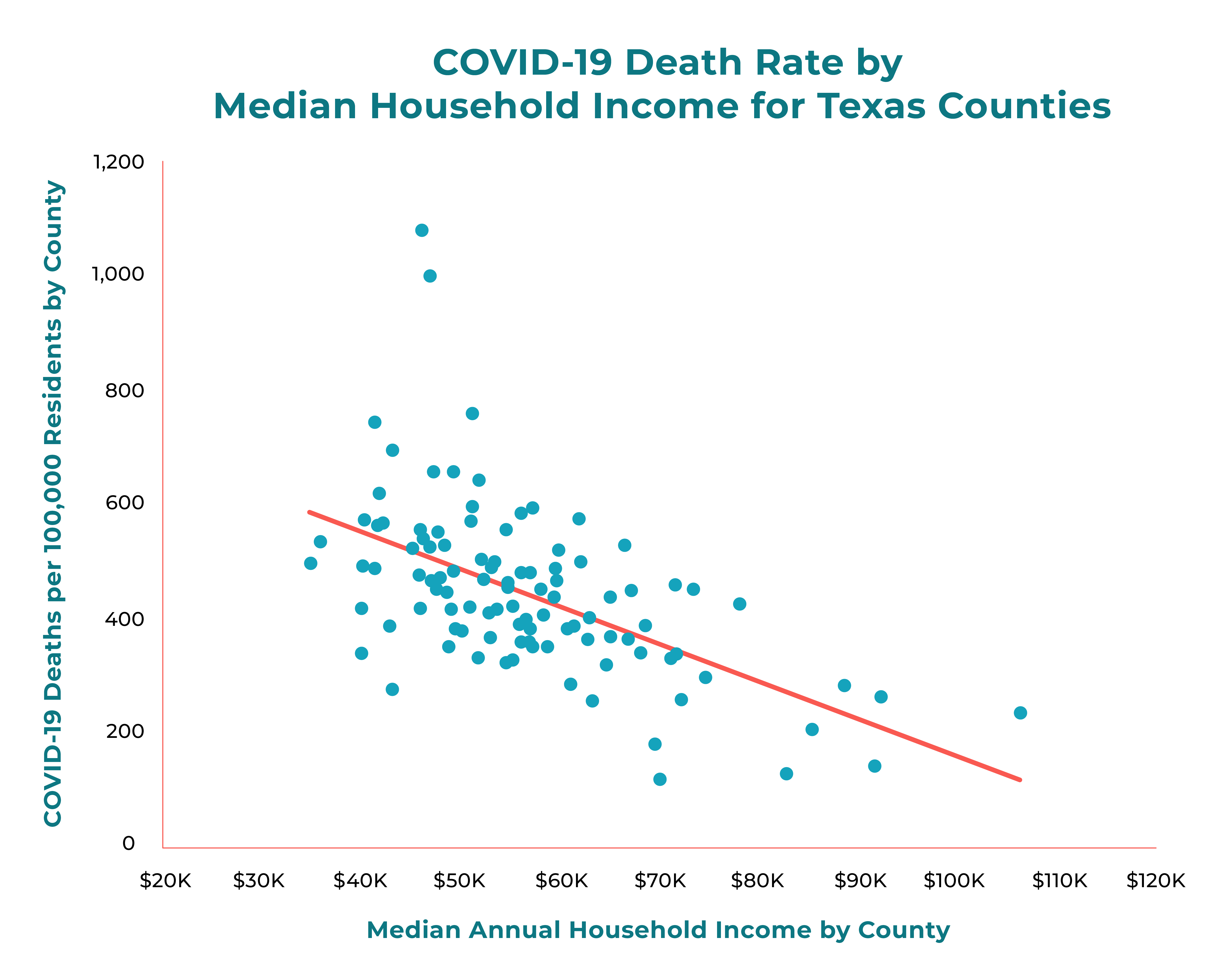

However, the greatest predictor of COVID-19 mortality is income. In Texas, there is a significant relationship between the rate of COVID-19 death and the median household income by county, so those more likely to die from the virus in Texas are disproportionately from low-income households.

The effect of loss on children

As outlined in the Hidden Pain report, losing a caregiver in any situation causes stress and trauma for the children left behind. Children who lose a caregiver exhibit increased rates of depression, addiction, suicide, unemployment, poorer academic results, and higher dropout rates.

Sudden deaths are more likely to lead to trauma and provide less time for support networks to coalesce around the child. While COVID-19 is an illness, death can occur relatively quickly while the caregiver remains physically isolated from loved ones. In contrast to illnesses like cancer, where there is often a period of treatment where children can engage and process the situation, the nature of COVID-19 does not allow children to say goodbye to their caregiver in person, denying them an opportunity for closure. Many could not even attend a funeral service.

As with any form of trauma, there are a number of factors that may contribute to a child’s ability to cope and recover.

The age of the child at the time of their loss influences the likelihood of a child experiencing negative outcomes. Children under five who lose a caregiver are at greater risk of experiencing negative impacts later in life than older children who experience loss, and generally the older the child, the more resilient they are likely to be.

As noted earlier, children of color are more likely to experience the loss of a caregiver to COVID-19, and ongoing negative effects are more likely for those children as a result of existing structural barriers such as substandard access to quality education, health care, and economic opportunities.

Immediate negative effects of caregiver loss could include financial hardship due to a reduction of household income, a decline in school performance , and the need to relocate to join a new caregiver, uprooting them from their existing community and support structures as they are processing their loss. Without appropriate and timely identification and intervention, there is an increased likelihood of academic underachievement, underemployment, drug dependency and interaction with the criminal justice system.

“The nature of COVID-19 does not allow children to say goodbye to their caregiver in person, denying them an opportunity for closure. Many could not even attend a funeral service.”

The effect of loss on children

As outlined in the Hidden Pain report, losing a caregiver in any situation causes stress and trauma for the children left behind. Children who lose a caregiver exhibit increased rates of depression, addiction, suicide, unemployment, poorer academic results, and higher dropout rates.

Sudden deaths are more likely to lead to trauma and provide less time for support networks to coalesce around the child. While COVID-19 is an illness, death can occur relatively quickly while the caregiver remains physically isolated from loved ones. In contrast to illnesses like cancer, where there is often a period of treatment where children can engage and process the situation, the nature of COVID-19 does not allow children to say goodbye to their caregiver in person, denying them an opportunity for closure. Many could not even attend a funeral service.

As with any form of trauma, there are a number of factors that may contribute to a child’s ability to cope and recover.

The age of the child at the time of their loss influences the likelihood of a child experiencing negative outcomes. Children under five who lose a caregiver are at greater risk of experiencing negative impacts later in life than older children who experience loss, and generally the older the child, the more resilient they are likely to be.

As noted earlier, children of color are more likely to experience the loss of a caregiver to COVID-19, and ongoing negative effects are more likely for those children as a result of existing structural barriers such as substandard access to quality education, health care, and economic opportunities.

Immediate negative effects of caregiver loss could include financial hardship due to a reduction of household income, a decline in school performance , and the need to relocate to join a new caregiver, uprooting them from their existing community and support structures as they are processing their loss. Without appropriate and timely identification and intervention, there is an increased likelihood of academic underachievement, underemployment, drug dependency and interaction with the criminal justice system.

“The nature of COVID-19 does not allow children to say goodbye to their caregiver in person, denying them an opportunity for closure. Many could not even attend a funeral service.”

What Children Need

Previous historic events that have caused the most death, destruction, and upheaval to Americans have been met with large-scale responses. The Civil War, the two World Wars, and the September 11 terrorist attacks each saw the federal government respond with support for those affected. The response to the COVID-19 pandemic should not be any different, particularly when children are the ones being left behind.

However, no large-scale response is happening to the current crisis. There has been no effort at the federal level to assist children who have lost caregivers, and there is only one proposed state bill in California to provide a modest trust for bereaved children. Meanwhile, support services like the Children’s Bereavement Center of South Texas, that specialize in working with children, are reaching their breaking points as they struggle to keep up with increased demand without a commensurate increase in funding while dealing with the same staff shortages every other industry across the nation is experiencing.

Federal and state governments must develop a package of supports that tackle both the immediate-term needs for children, as well as the long-term threat to educational, economic, and emotional well-being, including:

- Increased promotion of the COVID-19 Funeral Assistance program run by FEMA, with less bureaucracy and quicker reimbursement of funeral costs so families are not paying thousands of dollars out-of-pocket for any period of time

- Increased resources dedicated towards identifying children who have lost a caregiver to COVID-19, including the establishment and promotion of a hotline and accompanying website that can link children to support services

- A death gratuity, similar to what families of military members who die while on active duty receive, with a portion received immediately and a second portion held in trust for the child

- Increased government funding for grief and bereavement centers that specialize in working with children to help them meet the pandemic-related demand, including funding for grief camps and other bereavement programming

- Free access to ongoing clinical intervention for children—and their other caregivers—who are recommended for cognitive behavioral therapy

- For children not yet school-aged, affordable access to high quality early childhood education programs

- Access to an ongoing mentorship program

- Assistance with college applications and financial support through special scholarship funds or through a federal program similar to the GI Bill

- Increased access to ongoing employment support services, such as local or state programs that link job seekers to employers

It is also important for institutions to invest in ongoing research now to study the effects of pandemic-related caretaker loss on children, and the effectiveness of different programs. This is unlikely to be the last global pandemic or major event to cause a catastrophic level of loss; we need a clearer understanding of where efforts should be best directed to allow a fast and focused future response.

What Children Need

Previous historic events that have caused the most death, destruction, and upheaval to Americans have been met with large-scale responses. The Civil War, the two World Wars, and the September 11 terrorist attacks each saw the federal government respond with support for those affected. The response to the COVID-19 pandemic should not be any different, particularly when children are the ones being left behind.

However, no large-scale response is happening to the current crisis. There has been no effort at the federal level to assist children who have lost caregivers, and there is only one proposed state bill in California to provide a modest trust for bereaved children. Meanwhile, support services like the Children’s Bereavement Center of South Texas, that specialize in working with children, are reaching their breaking points as they struggle to keep up with increased demand without a commensurate increase in funding while dealing with the same staff shortages every other industry across the nation is experiencing.

Federal and state governments must develop a package of supports that tackle both the immediate-term needs for children, as well as the long-term threat to educational, economic, and emotional well-being, including:

- Increased promotion of the COVID-19 Funeral Assistance program run by FEMA, with less bureaucracy and quicker reimbursement of funeral costs so families are not paying thousands of dollars out-of-pocket for any period of time

- Increased resources dedicated towards identifying children who have lost a caregiver to COVID-19, including the establishment and promotion of a hotline and accompanying website that can link children to support services

- A death gratuity, similar to what families of military members who die while on active duty receive, with a portion received immediately and a second portion held in trust for the child

- Increased government funding for grief and bereavement centers that specialize in working with children to help them meet the pandemic-related demand, including funding for grief camps and other bereavement programming

- Free access to ongoing clinical intervention for children—and their other caregivers—who are recommended for cognitive behavioral therapy

- For children not yet school-aged, affordable access to high quality early childhood education programs

- Access to an ongoing mentorship program

- Assistance with college applications and financial support through special scholarship funds or through a federal program similar to the GI Bill

- Increased access to ongoing employment support services, such as local or state programs that link job seekers to employers

It is also important for institutions to invest in ongoing research now to study the effects of pandemic-related caretaker loss on children, and the effectiveness of different programs. This is unlikely to be the last global pandemic or major event to cause a catastrophic level of loss; we need a clearer understanding of where efforts should be best directed to allow a fast and focused future response.

Focusing Support in Texas

Few other states have experienced the level or rate of caregiver loss than Texas has. Our state also faces compounded challenges given its geographic size and large economic disparities.

To date, the state of Texas has not offered any assistance to children who have lost a caregiver due to COVID-19. Any decision to provide assistance should be focused first on areas of greatest need: the state’s major cities which have seen the largest loss of life, plus counties with lower-than-average household income that have recorded a significant number of COVID-19 deaths. Support should also be targeted to communities of color hardest hit by the pandemic.

Statistical analysis by CDF-Texas shows a correlation between Texas counties with low household incomes and the likelihood of higher COVID-19 death rates. While there is not a significant relationship between the percentage of Hispanic Texans in a county and the likelihood of COVID-19 deaths, Hispanic children are more likely to be in a low-income household and lose a caretaker; leaving them at higher risk of suffering compounded negative effects as a result.

Based on these considerations, these are the following counties we identified as the areas with the greatest need:

Harris County, Fort Bend County, Montgomery County, Travis County, Hays County, Williamson County, Bexar County, Collin County, Dallas County, Denton County, Ellis County, Hunt County, Kaufman County, Rockwall County, Hood County, Johnson County, Parker County, Somervell County, Tarrant County, Wise County, El Paso County, Aransas County, Nuances County, San Patricio County, Lubbock County, Webb County

Starr County, Hidalgo County, Willacy County, Cameron County

Maverick County, Taylor County, Potter County

Without additional and ongoing support and assistance, an entire generation of Texas and American children may face trauma and loss of opportunities. It is not too late to give these children the support they need, but we must act now.